Mæ’s winning project revives medieval tradition of treating older people with the dignity they deserve

By Ben Flatman 20 October 2023

This Stirling Prize winner places a much-needed focus on how we house and support people later in their lives

Source: Jim Stephenson

Source: Jim Stephenson

The John Morden Centre by Mæ Architects

Alex Ely references George Bernard Shaw as part-inspiration for the design of Mae’s Stirling-winning John Morden Centre in Blackheath: “We don’t stop playing because we grow old; we grow old because we stop playing.” It is an implied criticism of not only how we approach ageing as a culture, but of how we accommodate our elderly population.

The John Morden Centre seeks to address this failing head-on, by creating a social hub where older people can interact and live full social lives. But it is an exception.

The sorry truth is that most recent British architecture in this sector has too often been an afterthought. Housing for the elderly is sometimes found in repurposed Victorian villas, or buildings that look depressingly like storage facilities. Rarely is it in places that look like they were designed with the necessary care and consideration for the particular needs of older people.

Mae’s building shows us that it does not need to be like this, and that the spaces we create for this demographic can be inspiring and soulful. It is also an important reminder that – if we look back a little farther – this country has a rich history of creating often very special places that offer security, support and a sense of community for this demographic.

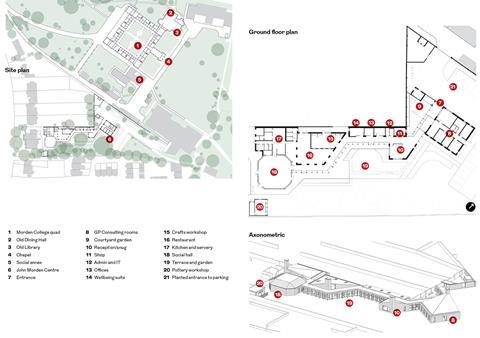

The John Morden Centre sits within the grounds of Morden College, a charitable foundation established in 1695. The handsome main building is sometimes attributed to Wren, but was implemented by the master mason, Edward Strong.

The architecture of Mae’s building imbues the new social and gathering spaces with many of the same values that inspired the design of the original buildings. They share a sense that life is to be treasured in all its stages, and that it can and should always be lived to its full extent.

Morden College can trace its origins to the medieval alms-houses, which were Christian charitable foundations, specifically established to provide support and relief to the elderly and poor. They first appeared in England as early as the 10th century.

Residents were usually required to pray for the souls of the founders who had built and endowed the almshouses. Through their promotion of a shared, communal life, combined with what was often beautiful vernacular architecture, they fostered a powerful sense of place and togetherness.

The idea of the alms house – essentially supported communal living for the elderly – may be a thousand years old, but it remains a powerful model for how to enable older people to live with dignity, self-respect, and varying degrees of independence.

We know that loneliness and a sense of isolation can be key contributors to poor mental and physical health in later life. The John Morden Centre builds on the strengths of the alms house model, with an added focus on social interaction and engagement.

Source: Mæ Architects

Source: Mæ Architects

Its spine-like enclosed “colonnade” twists through the length of the building, linking a café with a variety of flexible spaces that include a theatre. The colonnade references the original Morden College’s collonaded internal courtyard. Mae’s building also explicitly references the cloisters and courtyards of those even earlier medieval antecedents.

This project comes at a crucial time, when an ageing population requires us to think ever more carefully about the implications of later life. Mae’s own recent Daventry House project, which forms part of the Church Street masterplan in Marylebone, and provides 59 supported living flats for older people, demonstrates how the practice is leading efforts in the UK to reimagine this time-tested model for a wide range of contexts.

It is wonderful to see architecture for older members of society that seeks to give its inhabitants a sense of joy. As Morden College’s CEO, David Rutherford-Jones, observes: “It will enable them to feel good about themselves and about life… residents walking into John Morden Centre find themselves in a place that recognises their importance.” article ends